This week’s feature article is a guest post by Laura Bolling, who is interested in a variety of topics related to contemporary Japan, including manga literacy. She explores the benefits of using manga and anime in the classroom, as well as provides tips for implementing these unique resources for language and culture study. If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below!

—

As many of you visiting this site and reading this are no doubt aware, Japanese popular culture has seen a steady rise in popularity in recent years throughout North America and in Europe as well. The terms manga (Japanese comics) to anime (animated films/shows from Japan) are no longer obscure and many, especially youths, could likely recognize icons from one or two of the most popular shows, even if not by name.

This rise in popularity in manga presents language pedagogy with a unique opportunity. As popular series are being translated into many different languages, their use for teaching language is no longer restricted to just learning Japanese. Whether the series is from Japan, South Korea, China, or Taiwan, it’s fairly easy to find them at a relatively low cost in most bookstores in even Germany, France, or Italy in those respective languages. When in Germany last summer, I had a lot of fun reviewing my German while catching up on my favorite manga series. Though in ebook format manga availability is still somewhat limited (pedagogically useful titles all the more so), some can be purchased in various ebook forms from sites like Amazon.

Recently some experts have been finding that comics and manga can help develop multimodal literacies, encouraging students to develop skills in negotiating meaning between image and text (see Schwarz and Rubinstein-Ávila). In a society in which this is an increasingly important type of literacy, structured practice of their use in the classroom can be integral. It is important that students become accustomed to more visual means of learning, since this will help them adapt in the language they are learning to what they are experiencing in their daily lives. After all, what with the global use of graphically intense mediums and technology like the internet at an all-time high, the increased popularity of computer games/console games, and now tablet computers causing publishers to rethink and restructure their products (such as tablet magazines), if there was ever a time to sharpen one’s skills to aptly negotiate meaning between text and image, now is that time. Obviously one’s exposure to these mediums will vary from situation to situation, but with technology-enhanced learning tools and resources (and often ones that present themselves with a lot of graphics) on the rise, teachers can benefit from keeping up and helping their students cultivate the multimodal skills necessary for the future.

Using mediums that are popular can also help enliven lessons. Students will be more willing to engage the language presented in a given text if it appeals to them. A lot of programs are using the popularity of comics to promote literacy, as they have found that not only are students more willing to participate if they are excited about the lesson, but also the way in which comics work allow students to be exposed to a mode of communication that tends to mimic real life situations (see TheComicBookProject).

Using mediums that are popular can also help enliven lessons. Students will be more willing to engage the language presented in a given text if it appeals to them. A lot of programs are using the popularity of comics to promote literacy, as they have found that not only are students more willing to participate if they are excited about the lesson, but also the way in which comics work allow students to be exposed to a mode of communication that tends to mimic real life situations (see TheComicBookProject).

For example, in a particular panel, a character might make a statement using a particular gesture or facial expression. This is closer to real communication than simply reading a description of an expression or gesture, which may then involve more weighty language and might detract from the statement being made. It also allows students to more accurately convey and interpret context for words and grammar, and teachers can gauge the results to see if the students are doing so properly. In addition, many studies (such as the one by Stuart Webb referenced below) have shown that students are more likely to demonstrate better language retention in lessons where the language pieces and vocabulary are presented with more telling contexts. These contexts help generate stronger ties between the target and their linguistic functions intended for the lesson. Manga, with its potential for interactivity, ability to cater to alternative learning types, and the way it can bring life to depicted situations, can really lend itself to this end. I can recall my own experiences as a language student when my German professor brought in a German Sunday morning comic that contained a joke using a grammar structure we were learning. As we broke up in groups to read and talk about the comic, our class suddenly seemed to come alive, and we most definitely were able to get a better handle on the language piece at hand.

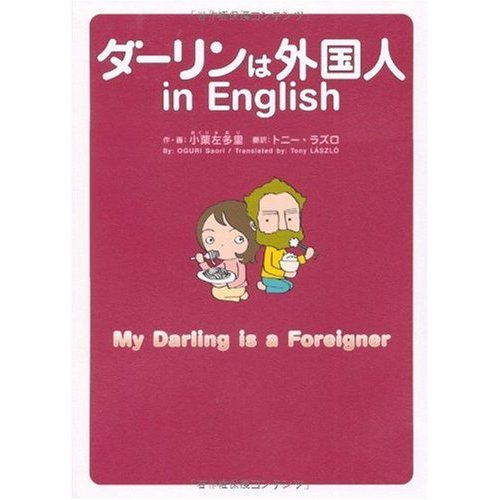

Using manga can also expose students to a wide range of cultural norms as illustrated in the content. Titles that depict experiences abroad can be quite useful for this and become the basis for meaningful classroom discussions on culture. I feel this is an important component of a language classroom, as culture and language are closely intertwined. If culture is not discussed frequently in the classroom, we do our students a disservice and fail to prepare them for intercultural engagement, which, after all, is the goal for many who are learning a foreign language. Titles such as Daarin wa Gaikokujin by Oguri Saori and later spin-off titles of the same author such as her travelogues (ie. Saori & Tony no Bouken Kikou: Hawaii de Dai no Ji and other related titles) can be a great source for this purpose. The “episodes” are not very long and the language is relatively easy, so readers will not get frustrated or mentally fatigued.

Using manga can also expose students to a wide range of cultural norms as illustrated in the content. Titles that depict experiences abroad can be quite useful for this and become the basis for meaningful classroom discussions on culture. I feel this is an important component of a language classroom, as culture and language are closely intertwined. If culture is not discussed frequently in the classroom, we do our students a disservice and fail to prepare them for intercultural engagement, which, after all, is the goal for many who are learning a foreign language. Titles such as Daarin wa Gaikokujin by Oguri Saori and later spin-off titles of the same author such as her travelogues (ie. Saori & Tony no Bouken Kikou: Hawaii de Dai no Ji and other related titles) can be a great source for this purpose. The “episodes” are not very long and the language is relatively easy, so readers will not get frustrated or mentally fatigued.

Four-panel comics and other shorter styles of comics may also be excellent resources for illustrating a grammar point. Not only are they short and simple, but often entertaining. Four-panel comics are frequently used as a format for gag comics. It isn’t long, but coupled with other activities, such as allowing students to make their own comics using the grammar point or perhaps with writing exercises might be an excellent way to work a comic into lesson and liven things up. This is what the folks who participate in TheComicBookProject do, and it’s obvious their students have a great time.

Practical considerations for bringing manga and anime into the classroom

It is also important to be mindful of the pitfalls in using manga and anime. One must not only be careful to gauge the subject matter of a particular clip or comic strip (in conservative countries, for example, titles with mature or culturally taboo themes may need to be avoided or utilized with caution, as it might detract from the lesson at hand or cause a stir with your superiors!), but also of the language level present in the chosen clip/strip. Ask yourself, “Is there language in this that my class may not know? Does this portion assume knowledge on behalf of the learner?” If it does, plan ahead. Either design classes that will lead up to the subject matter, whether grammatical, lexical, or cultural, presented in the chosen piece so that upon introduction students may use it with ease. Confusion can ruin a class, after all.

Choosing a title with subject matter in mind, titles such as Naruto and Bleach have become quite popular, but you might want to fish around and see what’s at the height of popularity at the time. However, they can be violent and there is a considerable amount of foreknowledge required for understanding the storyline. If you want to use it in class, try and choose a section that seems neutral in the storyline, such as a kitchen scene discussing food, or other culture-related situations. This will help utilize the appeal of its popularity, open discussion to cultural topics, and avoid alienating those in the class who may not be familiar with the series.

With the use of anime, you should check the audio-visual policies of a school or institution and make sure that they are not only approved for use, but also that the place you are at has the technology available for using them in the classroom (ie. projector, VCR, DVD player, etc.). Do not build a lesson using this unless you know you are going to be able to use it. Also, always prepare a back-up lesson without the technology, as you never know when something might go wrong. In the CELTA program I attended, one of our trainee’s entire lesson was ruined because the DVD she wanted to use didn’t have the proper region code for the DVD player they had. It’s good to be aware of these things if you plan to use audio-visual methods in the classroom.

I hope you will consider using manga or comics in your classroom. I think there are great benefits in their use not only to increase positive attitudes and feedback from students but also to enhance academic performance and material recall. I’m sure you’ll have fun as well.

It can be difficult to navigate what all is out there, so please feel free to consult the following free resources if you have any questions or concerns. They’ve certainly helped me.

– Professor Maureen Donovan, my graduate advisor, is infinitely knowledgeable about manga and is always putting interesting articles about panels and discussions, resources, and research regarding manga as well as digital information on her blog. I highly recommend bookmarking her Ohio State page, especially if you are in Japanese Studies. http://library.osu.edu/blogs/japanese/

– The University at Buffalo Library also has posted a great resource page, including sites for reviews as well as recommended book/comic lists (ie. list for teen readers). You can also explore comic history with the links they provide. http://library.buffalo.edu/asl/guides/comics.html

– “Librarian’s Guide to Manga and Anime” is a great page geared toward librarians, but with lots of useful information for anyone, including recommendations and advice on different series. http://www.koyagi.com/Libguide.html

– Openeducation.net has a good article with great suggestions on reads, and I find the comments to also be informative as people share suggestions of their own. http://www.openeducation.net/2008/02/14/manga–another–comic–format–worthy–of–classroom–consideration/

And of course, if you have any questions or comments for me, feel free to ask away in the comments section here as well.

Thanks for reading, everyone! I hope it’s been fun and informative.

Laura Bolling

External References:

Schwartz, Adam, and Eliane Rubinstein-Ávila. 2006. “Understanding the manga hype: Uncovering the multimodality of comic-book literacies”. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 50 (1).

Webb, Stuart. “The effects of context on incidental vocabulary learning.” Reading in a Foreign Language. 20.2 (2008): 232-245. Web. 23 Sep. 2011. <http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/October2008/webb/webb.pdf>.

http://tinyurl.com/amazon–manga–ebook–selection

Laura Bolling is an alumnus of Miami University in Oxford, Ohio where she got her BAs in German and Japanese. She finished her Japanese BA by doing the 11-week Asian Summer Studies Program at Temple University Japan in Tokyo. She got her CELTA certification from Randolph School of English in Edinburgh, Scotland in the summer of 2010 and also just completed her MA in East Asian Studies from The Ohio State University in June 2011.

An interesting idea. I’ve tried using manga before after a Japanese teacher recommended I show my students Dragonball in English. It was predictably much too difficult, but they really enjoyed the novelty. If there were very basic English four-panel comics easily available, I’d give it a shot.

Oops, looks like Laura’s reply got knocked down below rather than on a reply thread. Sorry about that!

Hello, Dom, and thanks for the reply.

I highly recommend a series called “Neko Ramen.” It’s not only adorable and funny, but they’re four-panel comics that you can just lift from the book. It’s not often that the panels are difficult to get without prior knowledge, and for the most part the contexts are clean.

You might even try getting a short comic strip and on a computer, scan it in and remove the texts in the bubbles and then allow the students to fill in the blanks using the English they know. That’s always a fun one, and then you’d get to see the creative side of your students.

If you try any of these, be sure to let us know how they go over and your suggestions based off your own experience. 🙂

This article is helpful and I am going to look at the links that you included as well.

I homeschool/unschool my 3 children. My daughter is 11 and has Aspergers and loves anime and manga. She has been sneaking to watch it and has been watching things that are not appropriate for her age. I have not problem with her watching it, but the content needs to checked by me before she watches it. In fact, Aspies like to watch anime because it helps them with being able to read others emotions. It’s easier for them to gain knowledge about feelings and facial expression.

In one of my unschooling groups some one mentioned using anime as a tool to learn cultural studies. So I am trying to put together something for my daughter so that she not only gets the desire that she has for anime feed, but also use it as a tool for additional learning.

Any specific ideas would be welcome. We have lots of technology and I am open to just about anything.

Pingback: Fueling Japanese Fluency with Manga and Anime – Languages in Common